Step 7. The next trick is mounting the

pieces to the wall. I wanted some depth and shadow in the piece, so the

three larger pieces are actually mounted between one and two inches out

from the wall. The downside is that it makes it more likely for people or

clothing to catch on the sharp points, which could be dangerous if the

piece was rigidly mounted. The solution is for each of the bigger pieces to

hang on a single screw sticking out from the wall, like a cheap wire

picture hanger. That way if anyone catches on a point the piece it will

move with them instead of poking or tearing clothing. This trick only works

if some part of the piece is above the center of gravity when hanging in

its final position: if the piece is "U" shaped (like the small

spur) then no matter where you put the hanger it will flip over.

First I found the balance point on each piece that would cause it to

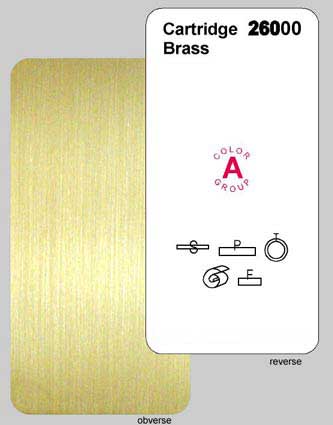

hang at the desired angle. Then I used two brass washers and some thin

brass wire to make a wire hanger for each piece. I looped the wire back and

forth alternately through the center of each washer, leaving a couple

inches between them. Then I twisted the loops to form a single stranded

wire. Finally, I glued the washers to the back of each of the three pieces

such that the center of the wire was at the center of gravity I'd located

earlier. JB Weld works well as a

metal-to-metal adhesive, and is available at most hardware stores.

Then I installed EZ

Anchors (available at most hardware stores) into the drywall at the

appropriate position, and inserted long #8 brass screws into the anchors

such that they poked out at the depth I wanted. Then I just hung each piece

like I'd hang a painting, and could adjust a little along their wire

hangers to make sure they were all positioned at the right angle.

As I mentioned above, the smallest piece didn't have an appropriate

place to attach a hanger, but luckily it was both light and intended to be

flush with the wall anyway. After briefly experimenting with gluing nails

directly to the back of the piece (didn't stick — the heads of the

nails didn't have enough surface area) I just stuck two normal sewing pins

into the wall so and set the piece on top of them (barely visible in the

rightmost picture, above). Then I cut the head of the pin and bent it

slightly to make the piece more secure. |